Moralejo Review Cranberry Products May Prevent Full Text

Cranberry Excerpt for Symptoms of Astute, Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection: A Systematic Review

Nuffield Department of Main Intendance Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Radcliffe Primary Care Building, Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, Woodstock Route, Oxford OX2 6GG, Britain

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: 26 November 2020 / Revised: 22 December 2020 / Accepted: 23 Dec 2020 / Published: 25 December 2020

Abstruse

Background: Constructive alternatives to antibiotics for alleviating symptoms of acute infections may be appealing to patients and enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Cranberry-based products are already in wide use for symptoms of acute urinary tract infection (UTI). The aim of this review was to identify and critically assess the supporting evidence. Methods: The protocol was registered on PROSPERO. Searches were conducted of Medline, Embase, Amed, Cinahl, The Cochrane library, Clinicaltrials.gov and WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. We included randomised clinical trials (RCTs) and non-randomised studies evaluating the result of cranberry extract in the management of astute, elementary UTI on symptoms, antibiotic employ, microbiological assessment, biochemical cess and adverse events. Report chance of bias assessments were made using Cochrane criteria. Results: We included 3 RCTs (n = 688) judged to be at moderate adventure of bias. One RCT (n = 309) found that advice to consume cranberry juice had no statistically pregnant event on UTI frequency symptoms (hateful difference (MD) −0.01 (95% CI: −0.37 to 0.34), p = 0.94)), on UTI symptoms of feeling unwell (MD 0.02 (95% CI: −0.36 to 0.39), p = 0.93)) or on antibiotic use (odds ratio 1.27 (95% CI: 0.47 to 3.43), p = 0.64), when compared with promoting drinking water. One RCT (n = 319) establish no symptomatic benefit from combining cranberry juice with immediate antibiotics for an acute UTI, compared with placebo juice combined with immediate antibiotics. In one RCT (northward = 60), consumption of cranberry extract capsules was associated with a within-group improvement in urinary symptoms and Escherichia coli load at day ten compared with baseline (p < 0.01), which was not found in untreated controls (p = 0.72). Two RCTs were under-powered to discover differences between groups for outcomes of interest. At that place were no serious agin effects associated with cranberry consumption. Conclusion: The current prove base for or against the use of cranberry extract in the management of acute, uncomplicated UTIs is inadequate; rigorous trials are needed.

one. Introduction

Women frequently experience symptoms attributed to urinary tract infection (UTI) [ane] and a high proportion receive antibiotic treatment [two]. Increasing antibody resistance has sparked interest in non-antibiotic treatments for common bacterial infections, such as UTIs [iii,4,5,6].

Cranberry fruit (Vaccinium macrocarpon) grows on evergreen shrubs that are native to Due north America [7]. Cranberry fruit is classed every bit a functional food due to the naturally loftier content of compounds, such equally polyphenols, which are believed to take antioxidant and therefore wellness-promoting properties [viii]. The reported health benefits of cranberry consumption range from cardioprotective effects due to improved cholesterol profiles [9] to aiding digestive health [10]. Cranberry exists in diverse forms, including the raw fruit (fresh and dried), cranberry juice and cranberry extract in capsule/tablet formulations [11].

Cranberry excerpt could be a potential culling to antibiotics to treat acute uncomplicated UTIs. Proanthocyanidin (PAC) with A-type linkages, or their metabolites, are believed to be the agile ingredient in cranberry, preventing Escherichia coli (Eastward. coli) from bounden to the bladder uroepithelium [12] and thereby reducing the power of E. coli to cause and sustain a UTI. Systematic reviews assessing the utilize of cranberry in the management of recurrent UTIs provide mixed evidence for do good [13,fourteen]. A 2012 Cochrane review of 24 trials (n = 4473) of men, women and children constitute that cranberry did not significantly reduce recurrent UTI compared with placebo, advice to increase h2o intake or no treatment. A subgroup analysis of women with recurrent UTI found that cranberry consumption resulted in a non-significant reduction in recurrent UTIs [15].

Whilst many studies have evaluated the effectiveness of cranberry extract in reducing recurrent UTI, few have assessed effects on symptoms of acute UTIs [16]. The aim of this systematic review was therefore to synthesise the evidence for the apply of cranberry products in the management of acute, unproblematic UTIs.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We conducted searches in Medline, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Amed, Web of Science and Cinahl from inception to tertiary Feb 2020. We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and Google Scholar for relevant studies. Search terms included, only were not limited to, cranberry, vaccinium and urinary tract infection (see Table S1 for the comprehensive search strategy). There were no language or time restrictions. We consulted experts in the area and manufacturers of cranberry products (Ocean Spray and Trophikos, LLC) to place relevant studies, and the bibliography of selected articles was hand-searched to find further eligible studies. Manufacturers of cranberry products had no other involvement in this systematic review. Each citation was independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (OAG and either JJL or EAS), with disagreements resolved by discussion.

two.2. Eligibility Criteria and Report Option

Nosotros included RCTs (blinded and open-characterization) comparing the effectiveness of cranberry extract with any other treatment for acute uncomplicated UTIs in patients aged 18 years and above. Non-randomised studies (including cohort studies, case–control studies and quasi-randomised studies) assessing the use of cranberry in treating acute UTIs were also eligible. For inclusion, cranberry extract needed to exist orally administered equally juice, fruit or as capsules/tablets/pills. In studies in which a cranberry product was combined with some other intervention/exposure, data allowing the effect of cranberry on the issue(southward) of interest to be isolated were required. Included studies needed to report at least one of our primary or secondary outcomes. Primary outcomes were assessment of participants' symptoms/clinical status/wellbeing assessment (e.yard., symptom burden or time to resolution of symptoms), antibiotic use (immediate and/or delayed) and clinical cure. Secondary outcomes were microbiological cure/cess; biochemical assessment; assessment of mechanisms of activeness; and cess of harms/adverse events.

We excluded studies of exclusively complicated UTI (e.chiliad., catheterised, self-catheterising, spinal string injury, renal tract abnormalities, male UTIs and pyelonephritis); studies assessing recurrent UTI; brute studies; example reports; and systematic reviews. Systematic reviews were used every bit sources for references.

ii.3. Risk of Bias

We assessed the risk of bias of included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [17]. Two reviewers (OAG and EAS) independently assessed the gamble of bias of included studies, with disagreements resolved through give-and-take. The hierarchy of show of included studies was classified according to The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2 criteria [xviii].

2.4. Information Extraction

Nosotros extracted data from included studies on study setting, participants, study elapsing, the intervention and comparator and the results. We reported the hazard of bias across the studies graphically using RevMan [nineteen] and used a summary table to present the results of included studies. The data were independently extracted by 2 reviewers (OAG and EAS), with disagreements resolved through word. We had insufficient data to perform data synthesis and therefore nowadays the results in narrative.

3. Results

3.1. Study Screening

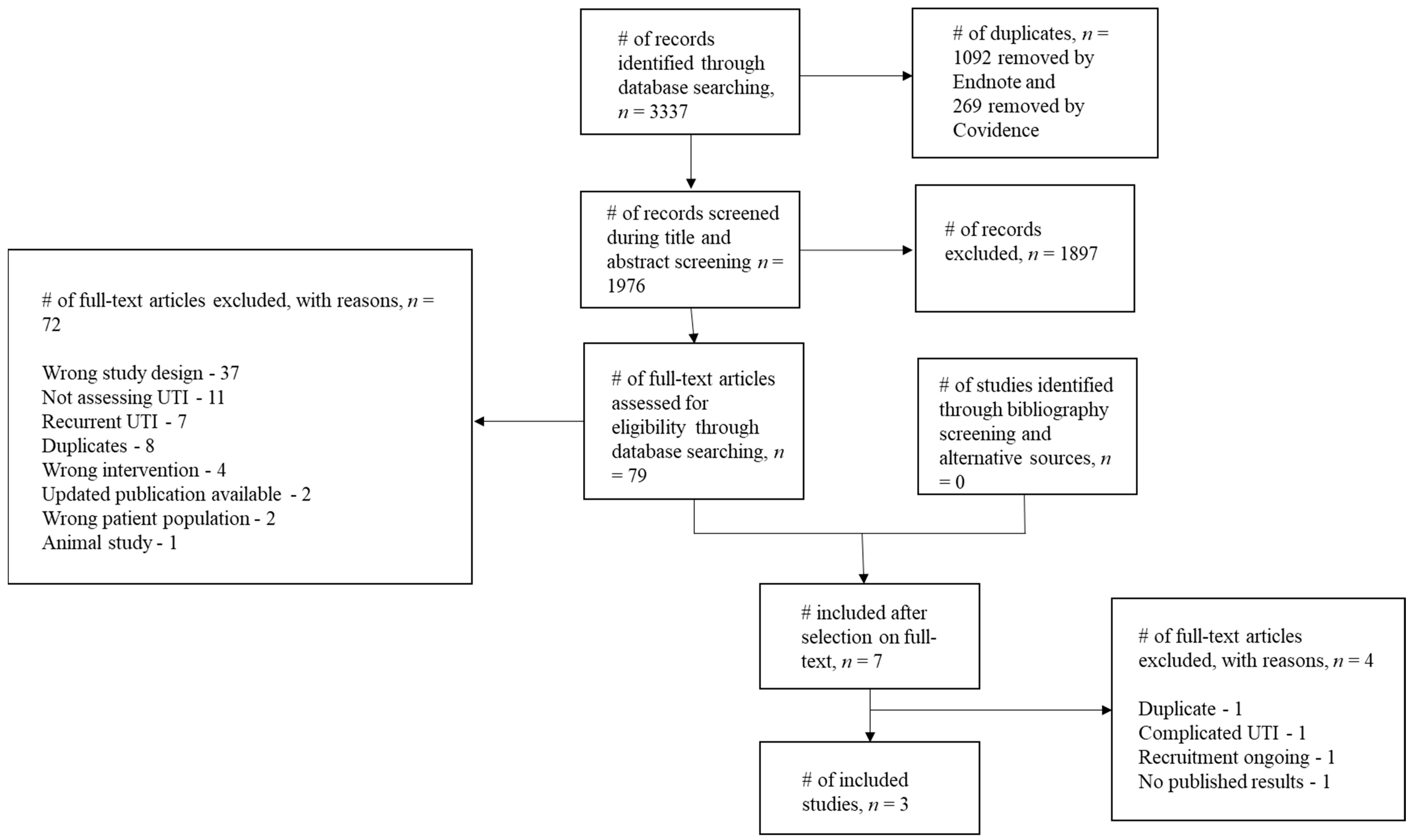

Electronic database searches identified 3337 results (Figure 1). Searching ClinicalTrials.gov, Google Scholar and WHO ICTRP did non place additional studies suitable for inclusion. Later removal of duplicates, 1976 citations were screened at the title and abstract stage and 79 eligible articles were identified. 30 vii studies were excluded because the written report design did not fit our criteria [12,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,fifty,51,52,53,54,55]; a number of these studies assessed the anti-adhesion effects of urine obtained from salubrious volunteers following cranberry consumption, when combined with uropathogen cultures ex vivo. Eleven studies were excluded as they did non assess UTI [56,57,58,59,threescore,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Seven studies were excluded as they assessed recurrent, rather than astute, UTI [67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. Four studies assessed an intervention that did not fit our criteria, such as cranberry extract combined with additional compounds [74,75,76,77]. 2 studies were excluded as updated publications were available for eligibility screening [21,78] and a farther two studies were excluded as they assessed the incorrect patient population [79,80]. I animal study was likewise excluded [81]. Eight studies were excluded as they were duplicates of 5 eligible studies [21,36,43,65,68]. Afterwards initially including seven studies, a farther four were excluded; one was a duplicate [82], the author of a 2d report confirmed that they included patients with complicated UTI [83], one was a trial registration of an ongoing RCT [82] and ane was a completed feasibility RCT with no published results [84]. Iii studies were therefore included in this review [85,86,87].

3.ii. Study Characteristics

All three RCTs were conducted in outpatient settings and included betwixt 60 [87] and 319 [85] participants (Table 1). One written report each was conducted in the Us [85], India [87] and the United kingdom [86]. The intervention used in two of the RCTs was cranberry juice [85,86], whilst the other trial used encapsulated cranberry powder [87]. The PAC content of the interventions varied greatly; participants in one study received between 7.5 (low dose) and 15 mg (high dose) of PAC daily [87], whilst participants in another study received on average 224 mg of PAC daily [85]. Ane study did not report the PAC content in the intervention [86].

The included RCTs provided information on outcomes relevant to this review; still, the primary objective of the studies was not assessment of cranberry extract for acute UTI. 2 studies focused on cranberry for preventing recurrent UTI [85,87]. Barbosa-Cesnik et al. recruited women with an acute UTI, treating the index UTI with immediate antibiotics and meantime randomly assigning the participants to receive either 8 ounces of 27% low-calorie cranberry juice twice daily or 8 ounces of placebo juice twice daily for six months [85]. Women were followed upward for 6 months or until they experienced a UTI, whichever came sooner. Sengupta and colleagues randomly assigned sixty women to receive either low-dose encapsulated cranberry powder (500 mg daily), high-dose encapsulated cranberry powder (k mg daily) or no treatment [87]. The principal outcome was the ability of the unlike handling regimens to prevent recurrent UTI over a 90-solar day period.

The primary objective of the trial by Niggling et al. was to determine the effectiveness of five treatment strategies in the management of suspected acute, simple UTI, with participants randomly assigned to: (ane) immediate antibiotics; (ii) delayed antibiotics; (3) antibiotics dependent on the participant's symptom score; (iv) antibiotics offered if the dipstick was positive; and (five) antibiotics targeted to according to midstream urine results [88]. Four forms of cocky-help advice were randomised beyond the five groups in a factorial design and included: (1) information leaflet with tips on self-assist; (2) communication to utilise over-the-counter herbal remedies; (3) advice to employ bicarbonate; and (4) communication to drink at least 3–4 litres per day and to make at least 1 litre of this cranberry juice or orange juice.

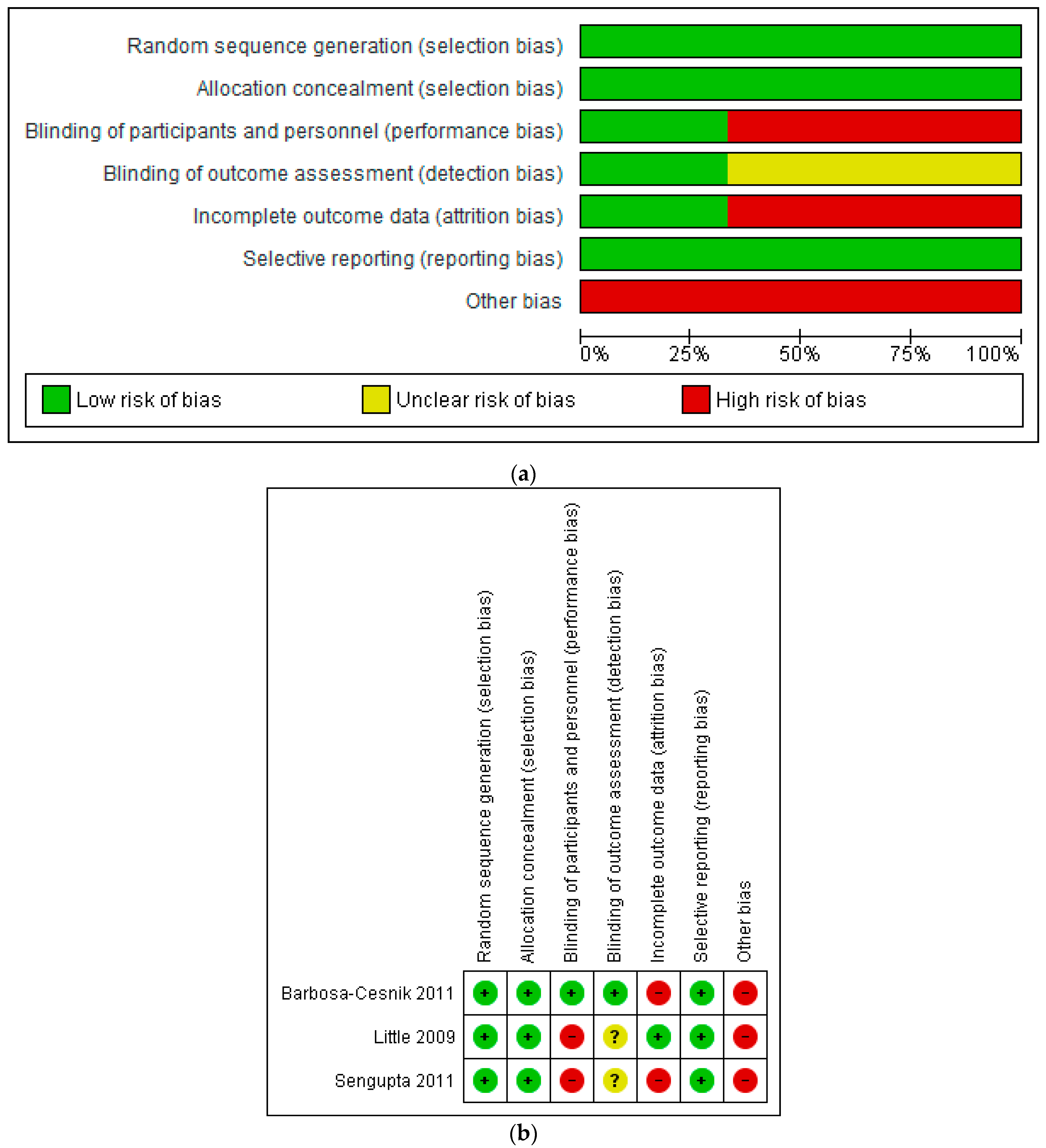

iii.iii. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias of included studies was judged equally moderate (Figure 2a,b), providing level ii (randomised clinical trial) evidence co-ordinate to The Oxford Levels of Testify 2 criteria [18]. All three studies were judged to have a depression chance of option bias and reporting bias. The RCT by Sengupta et al. is described by the written report authors as double-blind; however, women in the control group did not receive a placebo [87]. Information technology was therefore judged past the review authors to take a high risk of bias with respect to participant blinding. The open-label RCT by Little et al. was similarly judged to take a high risk of bias for this domain [86]. Two of the three RCTs were judged to accept a high take a chance of bias with respect to incomplete outcome data; Sengupta et al. [87] did not conduct intention to care for (ITT) analyses, whilst Barbosa-Cesnik et al. [85] conducted ITT analysis only had high attrition (26%).

Additional biases included cranberry industry involvement [85] and insufficient power to detect betwixt-group differences for cranberry comparisons [86,87]. According to the power calculation by Barbosa-Cesnik and colleagues [85], recruiting 120 participants in both arms would have provided the study with 80% power to detect between-group differences, bold that 30% of participants experienced a UTI during the follow-upwardly menstruum. In social club to accept into account greater loss to follow-upward that might occur in the cranberry group compared with the placebo group, the authors planned to recruit 200 participants per group (400 in total). Although 419 women were randomised, 100 women had negative urine cultures and were therefore non eligible for the study and did not receive cranberry or placebo juice. Therefore, 319 women were included in the ITT analysis—less than the authors had planned. Loss to follow-up was not higher in the cranberry group compared with the placebo group; however, recurrence of UTI occurred in 16.9% of participants—lower than anticipated by the authors—which may have adversely impacted the power of the written report.

3.4. Symptoms

Little et al. [86] analysed the impact of the unlike treatment strategies on "frequency symptoms" (day-time and night-time urinary frequency, dysuria and urgency) and "unwell symptoms" (restriction of usual activities, abdominal pain and feeling unwell). There was no significant event of advice to drinkable cranberry juice on the severity of frequency symptoms (hateful divergence (Dr.) −0.01 (95% CI: −0.37 to 0.34), p = 0.94)) or the severity of unwell symptoms (Doc 0.02 (95% CI: −0.36 to 0.39), p = 0.93)), compared with advice to drink water. Advice to potable cranberry juice compared with water did non touch the duration of symptoms rated moderately bad or worse—that is, rated three or more on a scale of zero to six (incident rate ratio (IRR) 1.18 (95% CI: ane.95 to 1.47), p = 0.13)).

Sengupta and colleagues reported a significant within-group improvement in symptoms at x days compared with baseline in both the high- and low-dose cranberry intervention groups, but not in the untreated controls [87]. No empirical data were presented to support this finding, nor were betwixt group comparisons reported.

Barbosa-Cesnik et al. [85] reported that at 3 days and at 1–2 weeks later enrolment in the trial, the presence of urinary symptoms and vaginal symptoms was similar between the cranberry and placebo juice groups. No empirical data were presented to support this finding. In this study, all women received immediate antibiotics to treat their index UTI; thus, the findings described represent the effect of cranberry juice in addition to immediate antibiotics.

3.5. Antibiotic Utilize

Petty et al. [86] constitute that advice to consume cranberry juice had no significant impact on the apply of antibiotics, compared with advice to drink h2o (odds ratio (OR) 1.27 (95% CI: 0.47 to 3.43), p = 0.64).

3.half-dozen. Microbiological Assessment

Sengupta et al. [87] reported a significant within-group reduction in E. coli load after ten days of handling with both depression-dose cranberry (p < 0.01) and high-dose cranberry (p < 0.0001), only not in the untreated controls (p = 0.72). At baseline, 4/xiii (30.8%) of the untreated controls were East. coli positive, whilst 14/21 (66.7%) of the low-dose cranberry group and 17/23 (73.ix%) of the loftier-dose cranberry group were E. coli positive.

3.7. Time to Reconsultation

There was no significant bear upon of cranberry juice consumption on fourth dimension to re-consultation compared with advice to drink h2o (adventure ratio (60 minutes) 0.74 (95% CI: 0.49 to 1.13), p = 0.17)) in the RCT by Lilliputian and colleagues [86].

3.8. Serious Adverse Events

There were no major adverse events (defined as major illness, admission to hospital, death) reported for any group in the trial by Fiddling et al. [86]. Sengupta et al. [87] similarly reported that no serious adverse events occurred during the course of the study. Barbosa-Cesnik and colleagues institute that serious adverse events occurred equally between groups, and none were deemed to be related to treatment received in the trial [85].

4. Word

The current evidence base for or against the use of cranberry excerpt in the management of acute, simple UTIs is inadequate. The existing, limited RCT evidence identified suggests that advice to consume cranberry juice does not ameliorate urinary frequency symptoms, feeling unwell or the elapsing of symptoms rated moderately bad or worse in women with astute UTIs, compared with encouraging the consumption of water. Advice to consume cranberry juice did not reduce the employ of antibiotics compared with promoting the consumption of water or time to re-consultation. In women receiving immediate antibiotics and cranberry juice, urinary symptoms were non reduced compared with firsthand antibiotics and placebo juice. Consuming encapsulated cranberry pulverization may reduce E. coli load and improve symptoms after ten days of consumption compared with baseline. The studies did not written report evidence of serious damage associated with cranberry consumption. These results must exist interpreted with caution as they come from a express number of studies with a moderate risk of bias for the outcomes of interest in this review, which were not the principal objectives of the trials.

four.i. Comparison with Existing Literature

We identified two trial registrations pertinent to this review. One of these trials, an open-label RCT in Spain, aims to recruit 128 women from emergency departments and outpatient clinics with acute UTI to assess the non-inferiority of astute treatment with a Cysticlean cranberry capsule (containing 240 mg PAC) compared with a iii-gram stat dose of Fosfomycin [82]. The primary event measures include a comparison of women experiencing "treatment failure" and patient-reported symptoms. The 2d study is an open-label feasibility RCT in the U.k., in which 46 women recruited from GP practices with symptoms suggestive of an acute UTI were randomly assigned to receive: (1) immediate antibiotics; (2) immediate antibiotics and cranberry capsules for upwardly to seven days (72 mg PAC per mean solar day); or (3) immediate cranberry capsules for up to 7 days (72 mg PAC per day), with a prescription of redundancy antibiotics in case symptoms did not improve with cranberry alone, or worsened [84]. The master outcomes of this feasibility trial relate principally to the ability to recruit participants, the ability to capture data through participant completed symptom diaries and the acceptability of the written report procedures and intervention to participants. Dissemination of the findings of these two studies should provide a useful improver to the electric current, express bear witness base and may serve as a platform for further enquiry assessing cranberry extract as a treatment for symptoms of astute UTI.

A Cochrane review assessing cranberry products for symptoms of astute UTIs, last updated in 2020, did not notice any eligible studies, nor did information technology identify either of the trial registrations discussed higher up [36]. This review therefore provides additional pertinent information.

Howell et al. [65] conducted a randomised double-blind study to determine the optimal amount of PAC to consume to provide E. coli anti-adhesion activeness in urine. Urine samples were collected from study participants earlier and afterwards consuming cranberry capsules containing varying amounts of PAC or placebo capsules. The anti-adhesion activity of the participants' urine was tested ex vivo against a uropathogenic Eastward. coli strain. There was a meaning increase in the anti-adhesion activity of PAC compared with placebo (p < 0.001), and the outcome increased in a dose-dependent mode. They determined that the optimal corporeality of PAC to consume was 72 mg per day. In the report by Piffling et al., the amount of PAC consumed past participants in the cranberry juice arm was non specified, and in the trial by Sengupta et al., participants in the high-dose cranberry group received 15 mg of PAC daily. Information technology is therefore possible that participants in the cranberry arms of these studies were consuming sub-therapeutic doses of what is believed to be the active ingredient in the intervention.

Some studies have found that advice to take not-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS) reduces the consumption of antibiotics for astute urinary tract infections, although they control UTI symptoms less effectively than antibiotics and patients had more than cases of pyelonephritis [three,4,vi,89]. Should cranberry prove to be an constructive handling for acute urinary tract infection, cranberry may confer sure advantages over NSAIDS, such as the appeal of consuming a natural production, as well every bit additional purported health benefits of cranberry within the urinary tract and elsewhere [eighty]. Potential harm associated with cranberry consumption, notwithstanding, must be considered. In that location is mixed evidence of an interaction between cranberry and Warfarin [ninety] and of an association with urolithiasis [91].

four.2. Strengths and Limitations

We employed a broad search strategy to maximise the chance of capturing relevant studies, including grayness literature. In addition to electronic database searches and trial registries, we contacted companies that sell cranberry products and experts in the field. When needed, we contacted authors of eligible studies to check whether they were suitable for inclusion.

However, nosotros recognise that there are limitations to this review. We identified few studies suitable for inclusion, with moderate risk of bias, and empirical data were non provided for all of the outcomes assessed in this review. This is probably in part considering cranberry extract as an acute UTI treatment was not the chief focus of the included RCTs. It is possible that we may take missed some studies that were suitable for inclusion, particularly unpublished studies. There was heterogeneity in the outcomes reported by the studies, and in the corporeality of PAC in the interventions used, making it difficult to make straight comparisons betwixt studies.

Two of the studies were nether-powered to determine the furnishings of cranberry on outcomes, which can atomic number 82 to exaggerated effect sizes [92]. One report had loftier attrition, and another did not comport intention to treat analyses.

I study reported within-group comparisons rather than betwixt-group comparison; this can lead to high Blazon I error (rejection of a true cipher hypothesis) and misleading results [93]. Whilst Little et al. [86] did not notice that cranberry improved UTI symptoms or antibody usage, the study authors noted that well-nigh half of the participants who were advised to drink water solitary reported drinking cranberry juice (49%). It is possible that "contagion" of the comparator grouping may have introduced Blazon Ii fault (non-rejection of a simulated nada hypothesis), making cranberry juice appear less constructive than information technology is.

four.3. Implications for Time to come Research and Clinical Practice

Few studies have assessed the utility of cranberry in treating symptoms of acute UTIs; further adequately powered, well-conducted randomised clinical trials are required. These studies should apply standardised interventions with a specified amount of PAC and must likewise report potential harm associated with cranberry consumption. It would also be helpful if the outcomes reported were standardised, to allow directly comparisons to exist made betwixt studies and meaningful meta-analysis of multiple studies to be performed. Given that cranberry extract is normally used by women for symptoms of acute UTI, disseminating the results of well-conducted studies evaluating cranberry extract as a treatment for astute UTI to both clinicians and the public will be of import.

There is a drive towards increasing the utilize of delayed antibody prescription for self-limiting bacterial infections in primary care [94]. In primary intendance, this strategy has been shown to reduce antibiotic prescription for acute respiratory infections by 40% [95] and for UTI by 20% [96]. If cranberry were plant to be constructive in robust clinical trials in managing acute uncomplicated UTIs, it could be incorporated into a delayed antibiotic prescribing strategy; women could be advised to take cranberry products initially, taking antibiotics only if symptoms fail to amend or worsen. However, in light of the very limited prove, no clinical recommendations can be fabricated at present.

5. Conclusions

There is a paucity of studies evaluating cranberry in the management of acute UTIs; none of the identified trials were primarily focused on cranberry as an astute UTI treatment. The existing studies are at moderate risk of bias. Evidence of the effectiveness and prophylactic of cranberry extract as a treatment for symptoms of acute, unproblematic UTI is inconclusive; rigorous trials addressing these outcomes are required.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

O.A.1000.—Protocol development, screening of abstracts, data extraction and assay, run a risk of bias assessment, and writing of the review. E.A.S.—Screening of abstracts, data extraction, risk of bias cess, and co-drafting of the re-view. J.J.L.—Protocol development, screening of abstracts and co-drafting of the review. C.J.H.—Protocol development and co-drafting of the review. C.C.B.—Protocol development and co-drafting of the review. E.A.S.—Screening of abstracts, information extraction, hazard of bias assessment, and co-drafting of the review. All authors take read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

O.A.G. is funded by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 203921/Z/16/Z) and the National Institute of Health Research School for Primary Intendance Research (grant number BZR00880 BZ01.49). E.A.S. is funded past the NIHR grant Improving the evidence-base for chief intendance: NIHR Evidence Synthesis working group extension, grant number 461. C.J.H. received funding support from the NIHR SPCR Testify Synthesis Working Group (projection 390) and the NIHR Oxford BRC. J.J.L. is funded by a NIHR clinical doctoral fellowship. The views are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Wellcome Trust, the NIHR or Section of Health and Social Care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nia Roberts for helpful discussions regarding the search strategy.

Conflicts of Interest

O.A.K. received grant funding from the Wellcome Trust and the National Institute of Health Research Schoolhouse for Primary Care Enquiry. E.A.Southward. and J.J.Fifty. have no disharmonize of interest to declare. C.J.H. reports he has received expenses and fees for his media work. He is Managing director of the CEBM at the University of Oxford, and Editor in Chief of BMJ Bear witness-Based Medicine and an NIHR Senior Investigator. C.C.B. is; a Senior Investigator of the National Institute of Health Research; Clinical Manager of the University of Oxford Main Care and Vaccines Collaborative Clinical Trials Unit of measurement; Clinical Manager of the NIHR Oxford Community Medtech and Invitro diagnostics Cooperative, and; salaried full general practitioner for the Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board. He has received funding from many public funding bodies for chief care research related to the management of common infections. He received payment for contributing to Advisory Boards for Pfizer in 2019, Roche Diagnostics in 2020, and for contributing to an Advisory Board for Janssen Pharmaceuticals about Respiratory Syncytial Virus treatment and vaccination from Janssen Pharmaceuticals in 2020, and holds an unrestricted grant form Janssen Pharmaceuticals for contributing to research on Respiratory Syncytial Virus.

References

- Lilliputian, P.; Merriman, R.; Turner, South.; Rumsby, Yard.; Warner, 1000.; Lowes, J.A.; Smith, H.; Hawke, C.; Leydon, One thousand.; Mullee, Yard.; et al. Presentation, pattern, and natural course of severe symptoms, and role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance among patients presenting with suspected elementary urinary tract infection in principal care: Observational written report. BMJ 2010, 340, b5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, C.C.; Hawking, M.K.; Quigley, A.; McNulty, C.A. Incidence, severity, help seeking, and direction of elementary urinary tract infection: A population-based survey. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 65, e702–e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.; Trill, J.; Simpson, C.; Webley, F.; Radford, Chiliad.; Stanton, L.; Maishman, T.; Galanopoulou, A.; Blossom, A.; Eyles, C. Uva-ursi extract and ibuprofen as alternative treatments for elementary urinary tract infection in women (ATAFUTI): A factorial randomized trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gágyor, I.; Bleidorn, J.; Kochen, Thou.Yard.; Schmiemann, K.; Wegscheider, Grand.; Hummers-Pradier, East. Ibuprofen versus fosfomycin for unproblematic urinary tract infection in women: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015, 351, h6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleidorn, J.; Gágyor, I.; Kochen, M.M.; Wegscheider, 1000.; Hummers-Pradier, Due east. Symptomatic handling (ibuprofen) or antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) for uncomplicated urinary tract infection?-results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Med. 2010, 8, xxx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronenberg, A.; Bütikofer, L.; Odutayo, A.; Mühlemann, K.; da Costa, B.R.; Battaglia, Thousand.; Meli, D.N.; Frey, P.; Limacher, A.; Reichenbach, S. Symptomatic treatment of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections in the ambulatory setting: Randomised, double bullheaded trial. BMJ 2017, 359, j4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polashock, J.; Zelzion, Due east.; Fajardo, D.; Zalapa, J.; Georgi, L.; Bhattacharya, D.; Vorsa, North. The American cranberry: Get-go insights into the whole genome of a species adapted to bog habitat. BMC Constitute Biol. 2014, 14, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szajdek, A.; Borowska, Eastward. Bioactive compounds and wellness-promoting properties of drupe fruits: A review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2008, 63, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruel, G.; Pomerleau, South.; Couture, P.; Lemieux, S.; Lamarche, B.; Couillard, C. Favourable touch on of low-calorie cranberry juice consumption on plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations in men. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, E.; Schaich, K. Phytochemicals of cranberries and cranberry products: Characterization, potential health furnishings, and processing stability. Crit. Rev. Nutrient Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 741–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodet, C.; Grenier, D.; Chandad, F.; Ofek, I.; Steinberg, D.; Weiss, E. Potential oral health benefits of cranberry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, A.B.; Reed, J.D.; Krueger, C.K.; Winterbottom, R.; Cunningham, D.G.; Leahy, M. A-blazon cranberry proanthocyanidins and uropathogenic bacterial anti-adhesion activity. Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.-H.; Fang, C.-C.; Chen, North.-C.; Liu, S.Southward.-H.; Yu, P.-H.; Wu, T.-Y.; Chen, W.-T.; Lee, C.-C.; Chen, S.-C. Cranberry-containing products for prevention of urinary tract infections in susceptible populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luís, Â.; Domingues, F.; Pereira, L. Can cranberries contribute to reduce the incidence of urinary tract infections? A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of clinical trials. J. Urol. 2017, 198, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepson, R.G.; Williams, G.; Craig, J.C. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Libr. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicariotto, F. Effectiveness of an association of a cranberry dry excerpt, D-mannose, and the two microorganisms Lactobacillus plantarum LP01 and Lactobacillus paracasei LPC09 in women affected past cystitis: A pilot study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 48, S96–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.1000.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration'south tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCEBM Levels of Testify. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.united kingdom/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (accessed on 26 September 2020).

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan)[Computer Program] Version five.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- AL-Zobaidy, M.A.-H.; Jebur, Grand.H.; Hindi, N.Thou.K. Development, Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activeness of the Aquatic Extracts of Zea Mays, Cranberries and Raisins against Bacterial isolates from Urinary Tract Infection in Babylon Province, Iraq. J. Indian J. Public Health Res. 2019, 10, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.B.; Vorsa, N.; Marderosian, A.D.; Foo, L.Y. Inhibition of the adherence of P-fimbriated Escherichia coli to uroepithelial-cell surfaces by proanthocyanidin extracts from cranberries. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1085–1086, Erratum in 1998, 339, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, M.; Diba, K. In vitro activity of cranberry extract confronting etiological agents of urinary tract infections. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010, 4, 286–288. [Google Scholar]

- Magariños, H.; Sahr, C.; Selaive, Southward.; Costa, M.; Figuerola, F.; Pizarro, O. In vitro inhibitory effect of cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpum Ait.) juice on pathogenic microorganisms. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2008, 44, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, E. Do Cranberries Aid in the Handling of Urinary Tract Infections? J. Acad. Nutr. Nutrition. 2002, 102, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPlante, One thousand.L.; Gill, C.M.; Rowley, D. Cranberry Capsules for Bacteriuria Plus Pyuria in Nursing Home Residents. JAMA 2017, 317, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eydelnant, I.A.; Tufenkji, N. Cranberry derived proanthocyanidins reduce bacterial adhesion to selected biomaterials. Langmuir 2008, 24, 10273–10281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherpour, A.; Noorabadi, P.; Abedi, F.; Taherpour, A. Consequence of aqueous cranberry (Vaccinium arctostaphylos L.) excerpt accompanied with antibiotics on urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli in vitro. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 2, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, A.; Souza, D.; Roller, Yard.; Fromentin, E. Comparison of the anti-adhesion activity of three different cranberry extracts on uropathogenic p-fimbriated Escherichia coli: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, ex vivo, acute report. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1934578X1501000720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Chiragh, Southward.; Tariq, S.; Alam, 1000.A.; Wazir, Chiliad.Due south.; Suleman, M. In vitro activity of vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry) on urinary tract pathogens in elementary urinary tract infection. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2015, 27, 660–663. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, G.; Chan, M.; Tufenkji, N. Inhibition of Escherichia coli CFT073 fliC expression and motility by cranberry materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6852–6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjany, N.; Senker, J.; Brandt, Southward.; Dobrindt, U.; Hensel, A. In vivo consumption of cranberry exerts ex vivo antiadhesive activity against FimH-dominated uropathogenic Escherichia coli: A combined in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro report of an extract from Vaccinium macrocarpon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8804–8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, E.; Chen, Y. Survival of Escherichia coli O157: H7, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes in cranberry juice concentrates at different Brix levels. J. Food Protect. 2007, 70, 2072–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, D.; Cronin, M.; Bell-ringer, J.; Freeman, S. Influence of cranberry juice on zipper of Escherichia coli to glass. J. Basic Microbiol. Int. J. Biochem. Physiol. Genet. Morphol. Ecol. Microorg. 2000, 40, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Caillet, S.; Côté, J.; Sylvain, J.-F.; Lacroix, One thousand. Antimicrobial effects of fractions from cranberry products on the growth of seven pathogenic bacteria. Food Control 2012, 23, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, P.; Agniel, R.; Gaillard, J.; Denys, P. Effects of cranberry juice on uropathogenic Escherichia coli in vitro biofilm formation. J. Chemother. 2005, 17, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepson, R.G.; Mihaljevic, L.; Craig, J.C. Cranberries for treating urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, iv, CD001322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolosi, D.; Tempera, K.; Genovese, C.; Furneri, P.Thousand. Anti-adhesion activity of A2-type proanthocyanidins (a cranberry major component) on uropathogenic Due east. coli and P. mirabilis strains. Antibiotics 2014, 3, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzaález de Llano, D.; Liu, H.; Khoo, C.; Moreno-Arribas, M.Five.; Bartolomé, B. Some new findings regarding the antiadhesive activeness of cranberry phenolic compounds and their microbial-derived metabolites against uropathogenic bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2166–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotchkiss, A.T., Jr.; Nunñez, A.; Strahan, G.D.; Chau, H.K.; White, A.K.; Marais, J.P.; Hom, Yard.; Vakkalanka, K.S.; Di, R.; Yam, G.50.; et al. Cranberry xyloglucan structure and inhibition of Escherichia coli adhesion to epithelial cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 5622–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnicz, D.; Tichaczek-Goska, D.; Korzekwa, K.; Kicia, Thou.; Hendrich, A.B. Report of the impact of cranberry extract on the virulence factors and biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis strains isolated from urinary tract infections. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 67, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Nikolic, D.; Pendland, S.; Doyle, B.J.; Locklear, T.D.; Mahady, G.B. Effects of cranberry extracts and ursolic acid derivatives on P-fimbriated Escherichia coli, COX-2 activeness, pro-inflammatory cytokine release and the NF-κβ transcriptional response in vitro. Pharm. Biol. 2009, 47, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González de Llano, D.; Esteban-Fernández, A.; Sánchez-Patán, F.; Martínlvarez, P.J.; Moreno-Arribas, Thousand.; Bartolomé, B. Anti-agglutinative activity of cranberry phenolic compounds and their microbial-derived metabolites against uropathogenic Escherichia coli in float epithelial cell cultures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, sixteen, 12119–12130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnicz, D.; Sycz, Z.; Walkowski, S.; Gabrielska, J.; Aleksandra, Westward.; Alicja, M.; Anna, South.-Ł.; Hendrich, A.B. Study on the influence of cranberry excerpt Żuravit S· O· Due south® on the properties of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains, their power to form biofilm and its antioxidant properties. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharf, B.; Sendker, J.; Dobrindt, U.; Hensel, A. Influence of cranberry excerpt on Tamm-Horsfall protein in human urine and its antiadhesive activeness against uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, J.; Caillet, S.; Doyon, G.; Dussault, D.; Sylvain, J.-F.; Lacroix, M. Antimicrobial outcome of cranberry juice and extracts. J. Nutrient Control 2011, 22, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermel, Yard.; Georgeault, South.; Inisan, C.; Besnard, Grand. Inhibition of adhesion of uropathogenic Escherichia coli bacteria to uroepithelial cells by extracts from cranberry. J. Med. Food 2012, 15, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Howell, A.B.; Zhang, D.J.; Khoo, C. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot written report to assess bacterial anti-adhesive activity in homo urine post-obit consumption of a cranberry supplement. Nutrient Funct. 2019, x, 7645–7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, K.L.; Howell, A.B.; Khoo, C. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to appraise the bacterial anti-adhesion effects of cranberry extract beverages. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Khoo, C. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Written report to Assess the Urinary Anti-Adhesion Activity Post-obit Consumption of Cranberry+ health™ Cranberry Supplement (P06-114-19). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, three, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Heong, South.; Chang, S. Effect of ingesting cranberry juice on bacterial growth in urine. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2006, 63, 1417–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.B.; Foxman, B. Cranberry juice and adhesion of antibody-resistant uropathogens. JAMA 2002, 287, 3082–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habash, G.B.; Van der Mei, H.C.; Busscher, H.J.; Reid, Thousand. The effect of h2o, ascorbic acid, and cranberry derived supplementation on homo urine and uropathogen adhesion to silicone rubber. Tin can. J. Microbiol. 1999, 45, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbinigie, O.; Allen, J.; Boylan, A.-M.; Hay, A.; Heneghan, C.; Moore, M.; Williams, N.; Butler, C. Does cranberry excerpt reduce antibiotic apply for symptoms of acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections (CUTI)? Protocol for a feasibility study. Trials 2019, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass-Ware, A.; Weed, D.; Johnson, T.; Spurlock, A. Evaluation of the consequence of cranberry juice on symptoms associated with a urinary tract infection. Urol. Nurs. 2014, 34, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafriri, D.; Ofek, I.; Pocino, M.; Sharon, Due north. Inhibition of lectin-mediated adherence of urinary isolates of Escherichia-coli past cranberry cocktail. State of israel J. Med. Sci. 1988, 24, 380. [Google Scholar]

- Avorn, J.; Monane, K.; Gurwitz, J.; Glynn, R.; Choodnovsky, I.; Lipsitz, L. Reduction of bacteriuria and pyuria with cranberry drink: A randomized trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1993, 41, 751–754. [Google Scholar]

- Habash, M.; Van der Mei, H.; Busscher, H.; Reid, G. Adsorption of urinary components influences the zeta potential of uropathogen surfaces. Colloids Surf. B-Biointerfaces 2000, 19, thirteen–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranberry Extracts for Urinary Tract Infections. Available online: http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ISRCTN32556347 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Lavigne, J.P.; Bourg, Thou.; Combescure, C.; Botto, H.; Sotto, A. In-vitro and in-vivo show of dose-dependent subtract of uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence after consumption of commercial Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry) capsules. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, P.; Agniel, R.; David, M.; Templer, C.; Gaillard, J.; Denys, P.; Botto, H. Reduction of Escherichia coli adherence to uroepithelial float cells after consumption of cranberry juice: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled cross-over trial. World J. Urol. 2006, 24, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avorn, J.; Monane, Yard.; Gurwitz, J.H.; Glynn, R.J.; Choodnovskiy, I.; Lipsitz, L.A. Reduction of bacteriuria and pyuria after ingestion of cranberry juice. JAMA 1994, 271, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botto, H.; Sotto, A.; Lebret, T.; Lavigne, J.P. Inhibition of Eastward. coli adherence to uro-epithelial cells by Urell Express®(Cranberry Compund): Comparative report vs placebo in healthy volunteers. J. Urol. 2008, 179, 84–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, L.; Perrelli, E.; Towle, V.; Van Ness, P.H.; Juthani-Mehta, M. Pilot randomized controlled dosing report of cranberry capsules for reduction of bacteriuria plus pyuria in female nursing habitation residents. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1180–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.B. Bacterial anti-adhesion activity of human urine after cranberry juice or pulverization consumption. In Proceedings of the 238th National Meeting & Exposition, Washington DC, USA, sixteen–twenty August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, A.B.; Botto, H.; Combescure, C.; Blanc-Potard, A.-B.; Gausa, Fifty.; Matsumoto, T.; Tenke, P.; Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.-P. Dosage issue on uropathogenic Escherichia coli anti-adhesion action in urine post-obit consumption of cranberry powder standardized for proanthocyanidin content: A multicentric randomized double blind study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, x, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peron, G.; Sut, Due south.; Pellizzaro, A.; Brun, P.; Voinovich, D.; Castagliuolo, I.; Dall'Acqua, S. The antiadhesive action of cranberry phytocomplex studied by metabolomics: Intestinal PAC-A metabolites just not intact PAC-A are identified as markers in active urines against uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Fitoterapia 2017, 122, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Dosage and Effectiveness Study of ShanStar® Cranberry Supplement for Prevention and Treatment against Women's Urinary Tract Infections. Available online: http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ISRCTN55813586 (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Ballester, F.S.; Vidal, Five.R.; Alcina, E.L.; Perez, C.D.; Fontano, East.Due east.; Benavent, A.M.O.; García, A.G.; Bustamante, K.A.S. Cysticlean® a highly pac standardized content in the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections: An observational, prospective accomplice study. BMC Urol. 2013, xiii, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Nieman, K.M.; Dicklin, M.R.; Schild, A.L.; Kaspar, K.L.; Khoo, C.; Derrig, Fifty.H.; Gupta, Grand.; Maki, Thou.C. Cranberry Beverage Consumption Reduces Antibiotic Use for Clinical Urinary Tract Infection in Women with a Contempo History of Urinary Tract Infection. FASEB J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranberry Juice for Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00093054 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Avorn, J.; Monane, M.; Gurwitz, J.; Glynn, R.; Choodnovskiy, I.; Lipsitz, L. Cranberry juice's effects on urinary tract infection. A condensed version of a Journal of the American Medical Clan written report on the effects of drinking cranberry juice on bacteriuria and pyuria. Community Nurse 1996, 2, 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Avorn, J. The effect of cranberry juice on the presence of bacteria and white blood cells in the urine of elderly women. In Toward Anti-Adhesion Therapy for Microbial Diseases; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1996; pp. 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- Stothers, L.; Dark-brown, P.; Fenster, H.; Levine, M.; Berkowitz, J. Dose response of cranberry in the handling of lower urinary tract infections in women: MP26-05. J. Urol. 2016, 195, E355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehmas, A.; ul Haq, Thousand.; Javed, M. Comparison of antibiotics and cranberry'southward effects in people having urinary tract infection (UTI). Indo Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 6, 7233–7237. [Google Scholar]

- Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Issue of Adjuvant Treatment with Compound Cranberry Extract Tablets (UmayC) in Acute Bacterial Cystitis. Available online: https://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Trial3.aspx?trialid=NCT00305071 (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Effect of Adjuvant Handling with Compound Cranberry Extract Tablets in Acute Bacterial Cystitis. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/bear witness/NCT00305071 (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Thiel, I.; Ardjomand-Woelkart, Yard.; Bornik, One thousand.; Klein, T.; Kompek, A. Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry) reduces intake of antibiotics in the treatment of non-severe lower urinary tract infections: A drug monitoring study. Planta Med. 2015, 81, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass-Ware, A. The Affect of Daily Consumption of Cranberry Juice on Symptoms of Urinary Tract Infections. Ph.D. Thesis, Troy University, Troy, Alabama, USA, May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of Cranberry Juice on Bacteriuria and Puria in Spinal String Lesion. Bachelor online: http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=IRCT201112073912N4 (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Papas, P.North.; Brusch, C.A.; Ceresia, G.C. Cranberry juice in the treatment of urinary tract infections. Southwest Med. 1966, 47, 17–xx. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, A. In vivo evidence that cranberry proanthocyanidins inhibit adherence of P-fimbriated E. coli bacteria to uroepithelial cells. FASEB J. 2001, 15, A284. [Google Scholar]

- Unmarried-Site, Open, Randomized Clinical Trial to Appraise the Not-Inferiority of Cysticlean® versus Fosfomicina in the Treatment of Cystitis in Women in Spain. Available online: https://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=EUCTR2018-001448-78-ES (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Greenberg, J.A.; Newmann, S.J.; Howell, A.B. Consumption of sweetened dried cranberries versus unsweetened raisins for inhibition of uropathogenic Escherichia coli adhesion in human urine: A pilot study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2005, 11, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranberries for Urinary Tract Infection. Available online: http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ISRCTN10399299 (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Barbosa-Cesnik, C.; Dark-brown, M.B.; Buxton, Thousand.; Zhang, L.; DeBusscher, J.; Foxman, B. Cranberry juice fails to prevent recurrent urinary tract infection: Results from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picayune, P.; Turner, Due south.; Rumsby, K.; Warner, G.; Moore, Yard.; Lowes, J.; Smith, H.; Hawke, C.; Turner, D.; Leydon, G. Dipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in urinary tract infection: Development and validation, randomised trial, economic analysis, observational cohort and qualitative study. Wellness Technol. Assess. 2009, 13, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, K.V.; Alluri, Yard.; Golakoti, T.V.; Gottumukkala, K.; Raavi, J.; Kotchrlakota, L.C.; Sigalan, S.; Dey, D.; Ghosh, South.; Chatterjee, A. A randomized, double blind, controlled, dose dependent clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of a proanthocyanidin standardized whole cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) powder on infections of the urinary tract. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2011, 7, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, P.; Turner, S.; Rumsby, Thou.; Warner, One thousand.; Moore, M.; Lowes, J.A.; Smith, H.; Hawke, C.; Mullee, M. Developing clinical rules to predict urinary tract infection in primary care settings: Sensitivity and specificity of near patient tests (dipsticks) and clinical scores. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2006, 56, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vik, I.; Bollestad, M.; Grude, N.; Bærheim, A.; Damsgaard, Due east.; Neumark, T.; Bjerrum, L.; Cordoba, G.; Olsen, I.C.; Lindbæk, M. Ibuprofen versus pivmecillinam for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women—A double-blind, randomized non-inferiority trial. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Oh, D.-S.; Jerng, U.K. A systematic review of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions of herbal medicine with warfarin. PLoS 1 2017, 12, e0182794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettman, G.T.; Ogan, K.; Brinkley, L.J.; Adams-Huet, B.; Pak, C.Y.; Pearle, M.South. Effect of cranberry juice consumption on urinary stone risk factors. J. Urol. 2005, 174, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas-Mallet, E.; Button, One thousand.S.; Boraud, T.; Gonon, F.; Munafo, M.R. Low statistical power in biomedical scientific discipline: A review of three human research domains. R. Soc. Open up. Sci. 2017, 4, 160254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Comparisons against baseline within randomised groups are often used and can be highly misleading. Trials 2011, 12, one–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Respiratory Tract Infections (Self-Limiting): Prescribing Antibiotics. Bachelor online: https://world wide web.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg69 (accessed on 4 Oct 2020).

- Picayune, P.; Moore, 1000.; Kelly, J.; Williamson, I.; Leydon, G.; McDermott, L.; Mullee, M.; Stuart, B. Delayed antibiotic prescribing strategies for respiratory tract infections in primary intendance: Pragmatic, factorial, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014, 348, g1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilliputian, P.; Moore, Yard.; Turner, S.; Rumsby, K.; Warner, G.; Lowes, J.; Smith, H.; Hawke, C.; Leydon, G.; Arscott, A. Effectiveness of five different approaches in management of urinary tract infection: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010, 340, c199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1. Menstruum chart showing the process for identification of studies eligible for inclusion.

Effigy one. Menstruation nautical chart showing the process for identification of studies eligible for inclusion.

Effigy 2. (a) Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each take a chance of bias particular presented as percentages across all included studies. (b) Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements nearly each adventure of bias item for each included report.

Figure 2. (a) Take chances of bias graph: review authors' judgements well-nigh each take a chance of bias detail presented equally percentages across all included studies. (b) Take chances of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies and cardinal results.

Table one. Characteristics of included studies and central results.

| Study ID and State | Blueprint | Participants and Setting | Number of Participants | Age (years) | Study Duration | Intervention | Control | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbosa-Cesnik et al. (2011), USA [85] | Randomised placebo-controlled trial | Women with an astute UTI (three or more than urinary symptoms) presenting for urinalysis at the University of Michigan Health Service laboratory with symptoms of UTI | 319 (155 received cranberry, 164 received placebo) | 18–40 | 6 months | 8 ounces of 27% low-calorie cranberry juice twice daily | 8 ounces of placebo juice twice daily | The presence of urinary and vaginal symptoms was similar between groups at iii days and at one–two weeks. |

| Little et al. (2009), UK [86] | Randomised controlled trial | Not-significant women presenting to General Practices in Due south-Westward England with a suspected elementary UTI | 309 (241 women in the juice comparisons: 75 advised to take cranberry juice, 78 advised to take orange juice, 88 advised to drinkable water) | 17–70 | Average follow-upward time of 575 days (range 35–968 days) | Advice to drink cranberry juice | Advice to beverage water | No significant touch on of communication to consume cranberry juice on the duration of symptoms rated moderately bad or worse (IRR 1.18 (95% CI: ane.95 to 1.47), p = 0.13), frequency symptom severity (hateful difference −0.01 (95% CI: −0.37 to 0.34), p = 0.94), severity of unwell symptoms (mean difference 0.02 (95% CI: −0.36 to 0.39), p = 0.93), employ of antibiotics (odds ratio ane.27 (95% CI: 0.47 to 3.43) p = 0.64) or time to re-consultation (hazard ratio 0.74 (95% CI: 0.49 to 1.thirteen), p = 0.17). |

| Sengupta et al. (2011), India [87] | Randomised controlled trial | Women with balmy symptoms of a UTI, urine culture positive and with a negative pregnancy test | threescore (xvi untreated controls, 21 received low dose cranberry, 23 received high dose cranberry) | 18–forty | xc days | Encapsulated PAC Standardised Whole Cranberry Pulverisation (PS-WCP)—500 (depression dose) and 1000 mg (high dose) | No treatment | Significant within-grouping improvement of symptoms at day ten compared to the baseline in both treatment groups, but not in the untreated controls. Pregnant within-group reduction in E. coli load in both treatment groups subsequently 10 days of treatment (depression dose, p < 0.01; high dose p < 0.0001; at a statistical significance level of 95%), simply not in the untreated controls (p = 0.72). |

| Publisher's Annotation: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open up admission commodity distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC By) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/10/1/12/htm

,

,

0 Response to "Moralejo Review Cranberry Products May Prevent Full Text"

Post a Comment